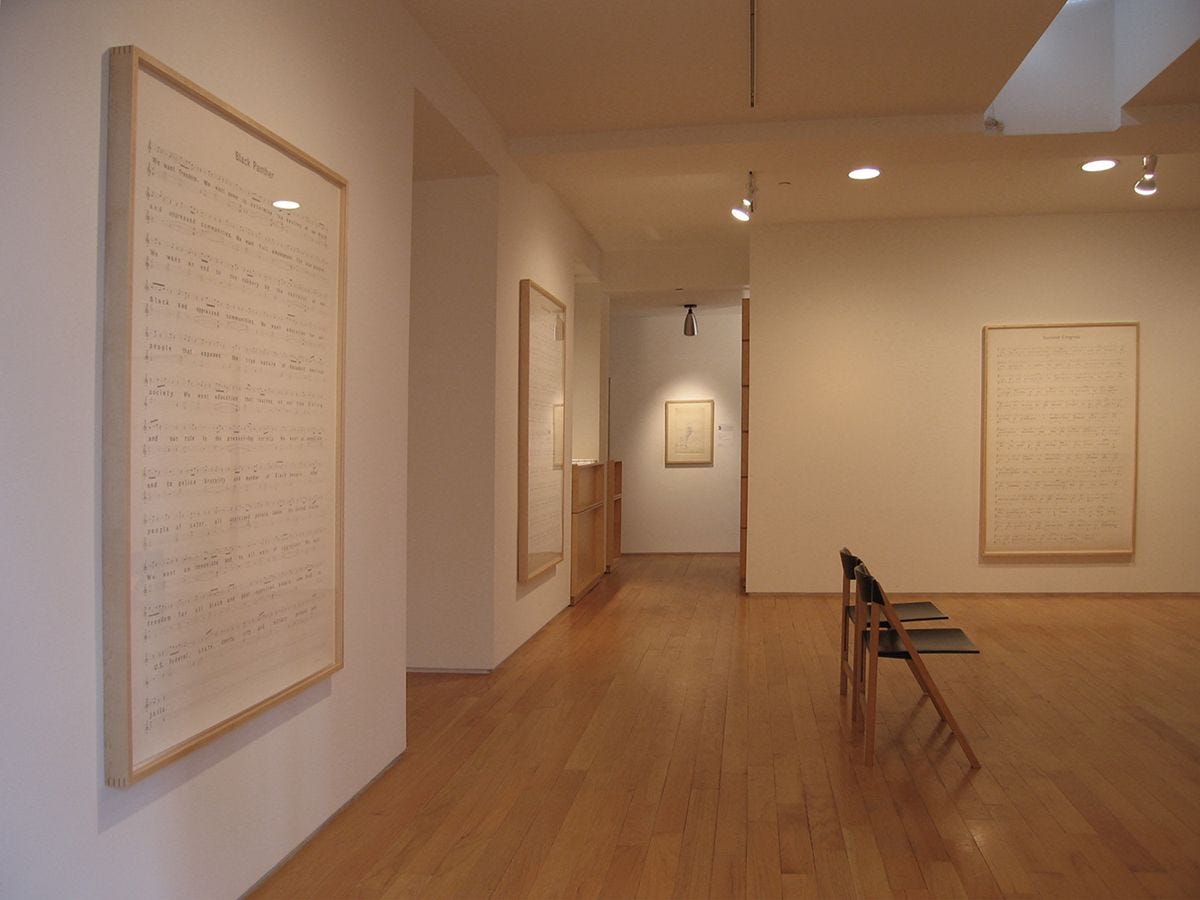

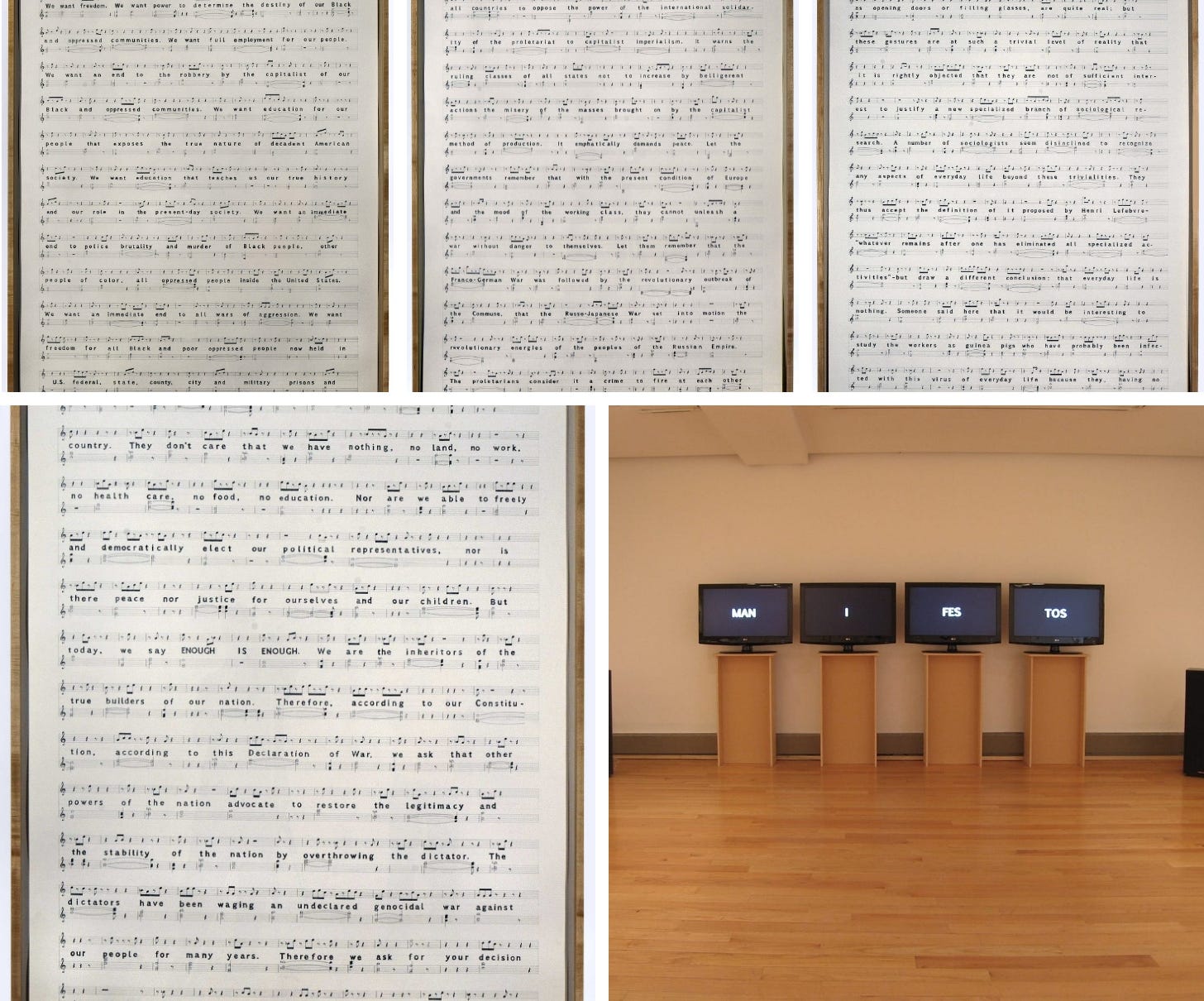

The American author Sylvia Wright (1917-1981), who at some point was editor of Harper’s magazine, worked in a journalistic tradition of social commentary and humor of which I consider myself a direct beneficiary. Some of her collected stories can be found in the book “Get Away from Me With Those Christmas Gifts, and Other Reactions” (1957) and the collection of novellas “A Shark Infested Rice Pudding” (1969). Most of her writings have been unfairly forgotten today. However, one little everlasting thing that Wright contributed to the English language is the coining of a term that was drawn from her essay “The Death of Lady Mondegreen.” As Wright recalls, when she was young her mother used to read outloud to her excerpt from Thomas Percy’s Reliques of Ancient English Poetry. One of the poems her mother would read was an old Scottish ballad titled The Bonnie Earl o' Moray, which contained the following section: Ye Highlands and ye Lowlands, Oh, where hae ye been? They hae slain the Earl Amurray, And layd him on the green. Wright, however, remembers that, hearing her mother recitation, the way she always understood the last line was “and Lady Mondegreen”. Wright writes: “I saw it all clearly. The Earl had yellow curly hair and a yellow beard and of course wore a kilt. He was lying in a forest clearing with an arrow in his heart. Lady Mondegreen lay at his side, her lung, dark brown curls spread out over the moss. She wore a dark green dress embroidered with light green leaves outlined in gold. It had a low neck trimmed with white lace (Irish lace, 1 think). An arrow had pierced her throat: from it blood trickled down over the lace. Sunlight coming through the leaves made dappled shadows on her cheeks and her closed eyelids. She was holding the Earl's hand. It made me cry.” Wright’s term, “mondegreen”, eventually made its way into becoming the term that describes misheard or misinterpreted words. Much has been written about how mondegreens are most common in songs, perhaps because the rhythm of a melody can obscure the normal structure of a spoken sentence thus opening it to misinterpretation. I had such confusion in grade school kid in Mexico, learning the Mexican national anthem. The first lines of the anthem are: Mexicanos, al grito de guerra/ El acero aprestad y el bridón/ Y retiemble en sus centros la tierra/ Al sonoro rugir del cañón. [Mexicans, at the cry of war,/ assemble the steel and the bridle,/ and may earth tremble to its core/ to the resounding roar of the cannon] I remember, as a kid listening to and trying to learn the anthem, thinking that the last line was instead “al sonoro rugir del camión” (the resounding roar of the bus). I sang it like that for quite some time until a teacher corrected me. In truth, in 1970s smog-filled Mexico City, the resounding roar of a bus with an un-tuned carburetor was a much more common and familiar image. There is a wealth of examples of musical mondegreens: in Celine Dion’s “My heart Will Go On”, where she sings ““I believe that the heart does go on” the line is sometimes replaced with “I believe that the hot dogs go on”; in Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody,” the line “spare him his life from this monstrosity” is sometimes sung as “saving his life from this warm sausage tea.” And in Adele’s “Chasing Pavements”, where she sings “or should I just keep chasing pavements”, it often is misheard as “or should I just keep chasing penguins.” Aside from its comedic aspect, what I find interesting is the new forms—poetic in their own way— that result from misunderstandings. A variation of this, not really in the area of mondegreens but more in a poor mechanical attempt at translation, is the 19th century phrase book “English as She is Spoke”, by Pedro Carolino. It is believed that Carolino did not speak English and thus used a Portuguese-French phrase book and a French-English dictionary to assemble his phrasebook. The result are a series of surreal phrases. Instead of the idiom “it’s raining buckets”, Carolino translates it as “it’s raining in jars”; “He is crawling” translates into “he go into four feet”. In effect, Carolino inadvertently created a metalanguage— and a masterpiece of unintentional humor. The natural question for me is whether we can find visual mondegreens. Roughly we would need to think of misunderstood images (not deliberately or ironically appropriated) that are applied in a different way to how they were intended. A close, but not exact, example might be the barber pole, the universal symbol of barber shops. Usually, a gyratory illuminated pole with red and white (and sometimes blue) stripes, it signals a business that does haircuts, usually for men. Its origin is medieval, when barbers also performed medical procedures like tooth extraction and bloodletting; the pole represented the one where a patient would hold on to for the objective of allowing blood flow. It is a symbol that continues connected to the original term, but its original bloody meaning has now been lost. Another example, this one not necessarily deliberate, which I will dare to suggest albeit not being a specialist on the subject, are the bowler hats that are often worn by Cholitas (indigenous women from Bolivia’s countryside). There are many legends regarding the adoption of the men’s bowler hat among the Cholitas, but many of them are variants of the story that it was an Italian hatter’s marketing ploy after being unable to sell a large shipment of bowler hats that had arrived from Europe, due to either their small size or color: he then augmented them with a colored ribbons and promoted them as an article of clothing specifically for cholitas, and the fashion caught on. However, this colonialist-flavored and rather patronizing story might not be accurate. According to Bolivian scholars, the first mention of Cholitas wearing men’s hats dates back to 1830, by Alcide d’Orbigny, a French naturalist who traveled through South America between 1826 and 1833. The felt hats the women wore at the time, according to historian Mauricio Sánchez Patzy, were also used by village women in the Argentinian provinces. So, while we do not for sure where the cholita bowler hat tradition came from, and whether it was deliberate repurposing or not, the fact is that the women embraced and re-gendered something that retrospectively looks like a visual mondegreen. The metamorphic process of the mondegreen thus contains a component of misunderstanding and misplacement of meaning, but the way it is resignified and collectivelly embraced in its new use the original misunderstanding becomes moot as does its apparent dissonance. Just because something meant A (e.g. This is a “man’s hat”) to others and now it means B (e.g. this is a “Cholita hat”), the original meaning of “A” becomes less relevant ( just like the original meaning of the barber’s pole). Producing deliberate mondegreens can be an interesting conceptual strategy. I intuitively ended up working this way sometime in 2012, when I was (as usual) sleuthing in the basement of a used bookstore and found an old archaeology book with exquisite black and white photographs of what appeared to be archaeological sites, each plate with a paragraph description. Dating from 1936, the book was in a language that I did not understand, but clearly was of Nordic/Scandinavian origin. I decided not to explore further, and simply attempt to (mis) translate the book based on how the words sounded to me. The result was a series of works produced with a poetic structure of which I really did not have so much control, even If I used my own subjective/imaginary interpretation of the words— I had to shape them to a somewhat textually (but not literally) coherent description. It resulted in texts like this: Plaque II. From behind its vision, the progenitor sees the world outside. In the middle of the borderline, it sees the anxiety. It rings every hour to bestow the conditions of the emaciated heuristic place, ringing until it bestows the same for every borderline. Flies by foot. The wilderness scalps its flight. Full of hours, usually, to the north. It strengthens its foreground as it sees its idleness, its background breaking loose. It forgets its own image. The book in question was Gamle Gardsanlegg I Rogaland (1936), by Norwegian archaeologist, Jan Petersen, a survey and study of medieval farm structures in the Western coastal region of Norway (and written, of course, in Norwegian). I had the great fortune that the artist Charles Gaines happened to see the work when it was first exhibited and he decided to write about it. In his observation, Gaines accurately detected my proclivity to be skeptical of any kind of authoritative explanations. He wrote: “for me, it shows that poetic conflations can problematically pass as truth statements. Once embedded within a scholarly apparatus that bears the stamp of authority, any proposition, no matter how fantastical, is imbued with a patina of truthfulness.” What the generous and modest Gaines did not mention in his comment was that in fact, unbeknownst to me at the time, in 2007-8, and at that exact same New York gallery he had developed a much better and artistically significant project employing translation strategies: his Manifesto scores. He took four revolutionary manifestos and transposed into musical notations dictated by a conceptual system of chord and chord notation; the music was written by dissecting the text and scoring as musical notation any letter in the text that was used as a music notation, letters A-H. Gaines picked four important revolutionary texts: the Zapatista and a Black Panther manifestoes, Guy Debord’s Situationist manifesto (“Perspective for Conscious Changes in Everyday Life”) and A Socialist Congress manifesto. A fifth score, which Gaines titled “Swarm”, combines the previous four. Gaines is quick to point out that he is not a composer, at least in the traditional sense: he writes, “ I don’t invent, create or change anything in the music, I do create the system and its code. But the system does the rest.”  Charles Gaines, Manifestoes Installation: Socialist Congress, Zapatista, Conscious Changes, Black Panther, Exhibition view, 2008. Courtesy Kent Fine Art It might appear that I am stretching the concept of mondegreen here, but— not least because the origin and nature of the original term is musical— Gaines’s alchemy, a deliberate engineering of accidental translation departing from a guiding rule that turns text into melody, does have in my view a mondegreen-like spirit. But of course, these works are much more than that. First, Gaines’s Manifestoes are, as a whole, an important metaphor about how guiding political ideals become, in their own way, the music score of a generation. This is likely the source of the famous idiom, “singing from the same hymn sheet” when referring to groups of people who are in agreement on a set of issues of which they give similar statements in public. And second, but not less important at least to me, is the idea that the process of repurposing language (and music) often assists social movements. This was true of the student movement of 1968 in Mexico City, where students took melodies of traditional Mexican popular and folk songs (which were familiar to everyone) and instead inserted lyrics connected to the movement’s slogan, which made it easier to spread. The questions that have emerged for me in recent weeks are: how can we harness the patterns of misunderstanding to build understanding? What is the soundtrack that we should build, not in spite of, but acknowledging the natural dynamics and potential offered by accidental misreadings? These questions are the more urgent because in this moment of virtue signaling and lecturing draw us toward less, not more clarity, we might need to consider counter-intuitive tactics. More than just fodder for humorous confusion, if used strategically, mondegreens may serve as a shattering tool of hardened perceptions. Invite your friends and earn rewardsIf you enjoy Beautiful Eccentrics, share it with your friends and earn rewards when they subscribe. |

Assisted Mondegreens

04:02

0