'There is no recipe, take it or leave it'Yemisí Aríbisálà on why there are so few Nigerian cookbooks. Illustration by Hannah Ekuwa Buckman.

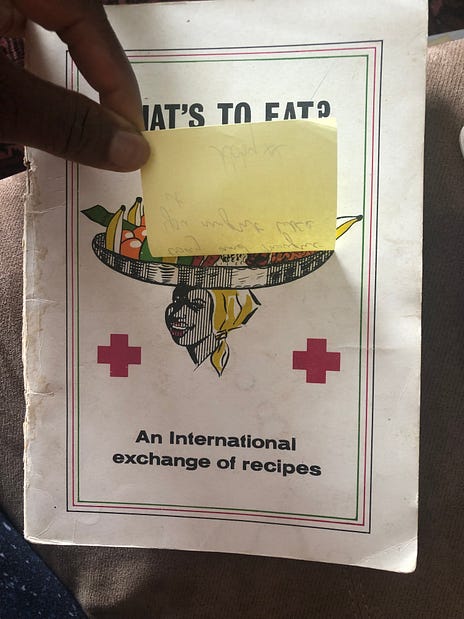

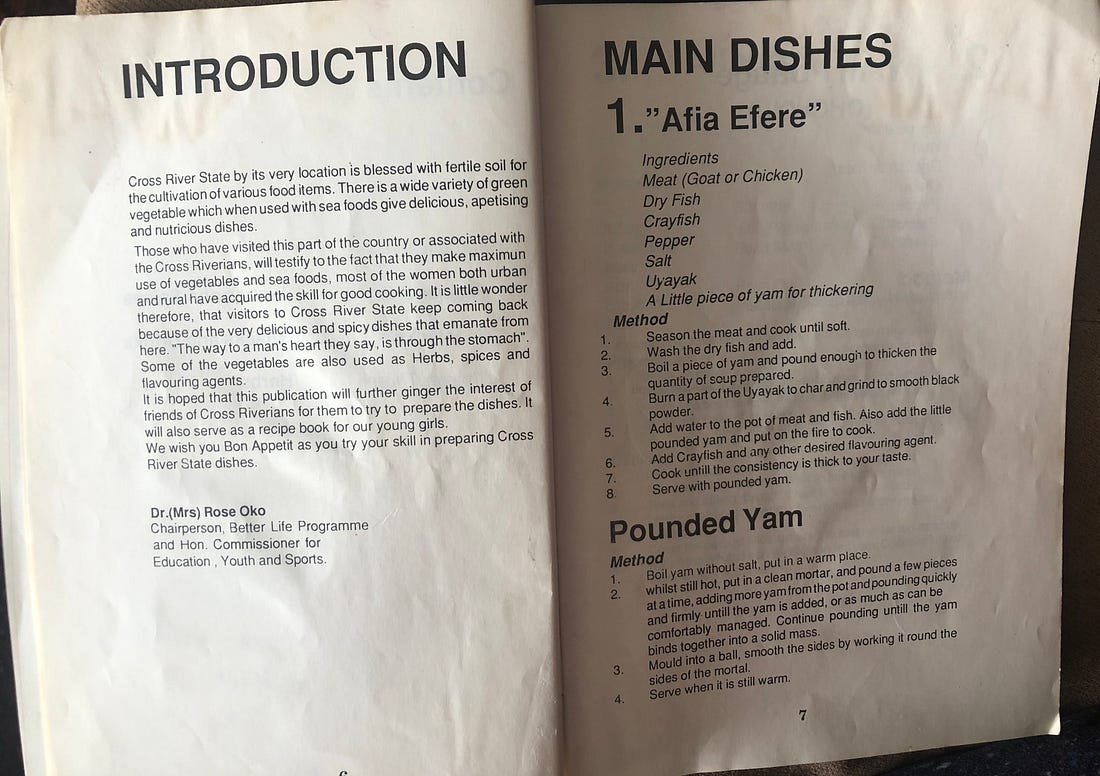

I have always been a terrible recipe writer. When my book Longthroat Memoirs: Soups, Sex and Nigerian Taste Buds was published in 2016, for months afterwards people wrote to me extensively about how the recipes in it had failed. In my defence, I wasn’t writing a cookbook, but a book about food in Nigeria, one of the most lucid windows into its culture, to talk about what is sacrosanct, taboo, vital – what we eat and why we eat. I concluded that although I had a good understanding of how food was woven into Nigerian life, I couldn’t translate recipes on to paper because I lacked some key skill (neither can I spell very well). But then again, I come from an environment where reticence – when it comes to recipes, and indeed other topics – was part of the landscape hundreds of years before I arrived on the scene. For five significant years when I was thinking about and writing my book, I lived in Calabar on the south-eastern coast of Nigeria – a lush city where there is cooking going on 24/7, a city full of lovers of pleasures but pretending not to be. Calabar, the capital city of Cross River State, is an excellent-enough example of non-stop cooking, but I suspect that to really meet the full-fat, interminable, slow-cooked meals that glorify that whole region – dishes like afang soup, ekpang nkukwo, and egome – you would have to travel inwards. Going north by road through small, Potemkin-towns like Akamkpa, Ogoja, Ugep, Yala, Okhanga-Mkpansi … on and on, just short of falling into neighbouring Cameroon. “In London, giving away your secret recipes in a book would be rewarded with money, publishing deals, maybe celebrity. In Calabar, withholding them would yield power and status and worship.” In Calabar, food is high calling plus seduction plus enterprise plus social mobility. There, you could never put anyone down for living in the kitchen – whether they were the hired help, the village Cinderella cooking as payment for being put up by a relative, or a long-suffering mistress competing with a Calabar man’s wife. The women of Calabar wear their gastronomic epaulettes with great arrogance, accumulating legendhood by cooking pots of palm oil-infused soups and pottages. One can imagine the kind of commitment to cooking that necessitates making your own palm oil in your backyard. These women become remarkably powerful in their communities in a way that reminds me of the celebrity cooks in London. It doesn’t directly translate, but it doesn’t have to. One such woman is Thelma Bello. Auntie Thelma is a powerhouse – the quintessential matriarch who catered every room of influence, fed every governor of the state since at least the early 90s. She walks with a stick, from a car accident in her twenties, not an old-age accessory. In all the years I knew her, I never heard Auntie Thelma raise her voice, something one would expect often from a personality who ‘womaned’ large kitchens. Hers was a great confidence, worn by a woman seemingly always holding her cards to her chest. One of the first unforgettable dishes of Auntie Thelma’s cooking I tasted was her fisherman’s stew at Ths Le Chateau Thelpim Hotels in the early 2000s. You would place your order, then wait to collect it in a small, plain room containing a few tables and chairs, and gyrating ceiling fans, on one side of the hotel compound. The stew looked simple enough – different kinds of whatever white fish was available, and prawns sourced from the Atlantic a few miles out from the Calabar river, cooked in a red stew with palm oil and a sprinkling of ntong leaf and iko leaf. But there was something especially delicious about the stew’s mouthfeel. I felt it skate on the tongue, with an unusual, beautiful smoothness and velvety texture, like an intimate handshake. After months of spending a small fortune on containers of fisherman’s stew from her at lunchtime, I decided to ask Auntie Thelma for her recipe. I knew I needed to approach this tactically, having already experienced disdain from other elderly women from Calabar when asking for recipes. In Calabar, there would be a clear withdrawal when a request for methodology was made. For the record, I had already tried my hand at Auntie Thelma’s stew and failed to reproduce it. I had tried ‘everything’ – different ways of blending the peppers and tomatoes, different cooking times, different textures of fish, different points of adding the oil. The only time I came close to the original’s mouthfeel was when I added a rogue ingredient. With it, the stew was not exactly like Auntie Thelma’s own, not quite there, but close enough. How do I know it was a rogue ingredient without having a confirmed recipe? Because once before, I had slipped in the question to Auntie Thelma. ‘Auntie Thelma, what is the recipe for your fisherman’s stew?’ She smiled without missing a beat and said: ‘Oh, it’s just a simple addition of … this and this and that and that … ’ The rogue ingredient was a pinch of ground dried bush mango seeds – what we call ogbono – which Auntie Thelma had not mentioned. When added to the blended cooked peppers, before putting the fish in, the ogbono changed the viscosity of the stew, substantially smoothening its mouthfeel. When I saw Auntie Thelma after this close replication, I blurted it out like a five-year-old, with barely hidden accusation and pain in my voice after so many failed attempts. You would think Auntie Thelma would have matched my enthusiasm by confirming it was the secret to the stew’s texture, or finally just putting me out of my misery by giving me the real recipe. But she merely smiled and said: ‘Hmm, hmmmm, that might work.’ But this is how it is. There is no recipe, take it or leave it. What is the word for ‘recipe’, in any case, in Efik or Ibibio languages? To say it in English is to identify yourself as a stranger, and to immediately feel the breeze preceding a slamming door. Obviously, if one hangs around enough, and becomes trusted, the prize of intimacy would be learning by seeing and tasting. In London, giving away your secret recipes in a book would be rewarded with money, publishing deals, maybe celebrity. In Calabar, withholding them would yield power and status and worship. I’ve always wondered how the cookbook industry in the northern hemisphere manages to generate so much material, so many twists upon twists for such a small percentage of people who actively cook, and yet, in Nigeria, there are no dedicated cookbook publishers, no million-dollar, three-book celebrity tie-ins. There are only a few cookbooks focused on Nigerian food, most of them published outside the country and inaccessible or unaffordable to the majority of women who cook. There are no long-running food programmes on TV, no Books for Cooks. But there are still similar power dynamics moving around, up and down, animating hundreds of thousands of bodies, creating ‘superstars’ and ‘celebrities’ and millionaires in their own rights and on their own terms. Fundamentally, there is no difference in ambition between the Calabar woman whose powers are firmly rooted in cooking for her community, family and business and the chef and cookbook writer in London with a book deal. Ambition, aspiration and power mean the same in every language in the world, but how it applies to food is affected by cultural beliefs.  Onitsha Market Literature There are laws that protect copyright in the European cookbook-writing world. Who will protect the rights of the Calabar woman with an outstanding, innovative recipe if she tells it to everyone? Here, there is a significant problem of documentation – of writing down the ‘how’ and ‘how much’ in recipe form. It is a pertinent one, since our language(s) are historic and alive, we have more than 500 mother tongues from 36 states. Google speaks Yoruba scrappily, and Onitsha Market Literature (for example), written in the 1950s and 60s in south-eastern Nigeria and used for publishing stories, pamphlets and handbooks, is revered among the Igbo people for its clarity of time and place. All this means that we could have written down recipes in our own tongues, and produced hundreds of cookbooks, if we had wanted to. “It is amazing to look at London through the eyes of a Calabar woman and hear her ask: what is the point of the recipes and all the beautiful plating, the smear, foam, smudge, and the small portions? What is all this talking around pots of food on television cooking?” One of the reasons we don’t have a library of cookbooks must be our unhappy relationship with the English lingua franca that the colonisers left behind. All kinds of magic can happen when we translate love into writing, whether a man’s love for a woman or a cook’s love for their food. But we have never gathered feeling and passion for eating and cooking under the umbrella of the coloniser’s tongue, not even in pidgin English. Therefore the language of cooking is still transitioning into the global, contemporary vernacular of recipes, ingredient translations and cookbooks. A Nigerian cookbook would ideally have to embrace multiple languages and dialects, as well as English and pidgin English, like the Maggi cookbooks attempted quite successfully in the 1980s, supplemented with weekly television shows. As much as we want the rest of the world to stop presuming that our food doesn't have a vocabulary – a repository of ideas, stories and myths – there is also a discomfort around food and sensuality, or a certain sense that is is somehow inappropriate to lavish praise on the experience of eating. For instance, it might be OK to go on and on about how delicious a dish is in English, but there could be a vulgarity to doing it in Yoruba. I have to admit to loving the parallels. Calabar’s women are aware of London’s epicurean manifestations, but they do not strain for any part of it. It is amazing to look at London through the eyes of a Calabar woman and hear her ask: what is the point of the recipes and all the beautiful plating, the smear, foam, smudge, and the small portions? What is all this talking around pots of food on television cooking? There’s nothing at all to write home about, she says. I have watched as Calabar’s magnificent gastronomic talents and icons bypass certain paradigms and goals without even a passing glance, without the same desire for power and positioning that these European chefs possess and chase. In London, the constant twisting and turning of recipes might be considered some unique form of genius, but in Calabar, a woman will hone a recipe to the greatest height of flavour, to a place where it is not tweaked endlessly, a place we might refer to as virtuosity. These ‘ways of cooking’ aren’t on global (western) media, not on cable television – but that is not fundamental. In Calabar, just because it isn’t all written down doesn’t mean it’s less exceptional, or that its enchantment is in any way diminished.  Three new-school West African cookbooks Now I live in London, within Anglophone-language food cultures, those that organise themselves in a way that is most familiar on global social media. Here in the UK, food is eulogised as a creative construction, a wonderful cultural punnet, but I have to remind myself that this only really represents a small part of the world. I am fascinated at my own ability to forget so easily – after all, I have only been back in the UK for six years, and before that I lived in another distinctive food culture that felt buried when you exit it. Incidentally, in another Somerset – the town of Somerset West, in the Western Cape in South Africa. I think about when I wrote a food column for a newspaper called 234 Next from 2009 to 2011, where the online comments section grew into a voluble dining table. Here, people didn’t hold back – they came and told me off without any reservations. They told me that I didn’t know how to cook Nigerian food, and I was a pretender, and that my lovely writing was what kept me relevant, if I was indeed relevant … People gave suggestions on cooking, corrected cultural standpoints, grew aggravated, and insulted somebody, or everybody. It was wonderful. A newly born, in-between world sprang up around 2016. In the UK, it produced books such as Lope Ariyo’s Hibiscus, and one of my favourite cookbooks, The Groundnut Cookbook by Duval Timothy, Jacob Fodio Todd and Folayemi Brown. Even though Ozoz Sokoh, AKA the Kitchen Butterfly, has not yet published a Nigerian cookbook (she is about to, this month), her blog goes back to that period, and is one of the best reference points in existence for Nigerian food. I have already mentioned the ‘original’ Maggi Family Menu Cookbooks, compiled from the popular 1980s television series, and the only ones published in Nigeria. Yemisi S Odusanya AKA Sisi Yemmie’s Nigerian Soups, Stews and Sauces is published via Amazon. But even now that there are several members of this new Nigerian cookbook world, what is missing is a cohesiveness, whereby the cookbooks converse together, bringing in the powerful intelligence and voice of the Nigerian on the streets of Nigeria. It feels at the moment that we are speaking from dining tables in other countries in the world, as Nigerians in diaspora, monologuing or conversing in passing. But like the 80s Maggi cookbooks, there were other unique spaces where the Nigerian recipe attempted to take shape. There is a lovely niche of cookbooks produced by Nigerian women’s groups that came together through churches, government programmes and organisations such as the Nigerian Red Cross. One of these was published by a programme called Better Life For Rural Women in 1987, an extensive (and expensive) programme to help rural women launched by Maryam Babangida, the enterprising wife of a military dictator, who we also call the first First Lady of Nigeria. (Indirectly, this meant that a lot of money was given by international bodies such as the United Nations to the first lady for things that made her look busy and admirable.) Babangida’s initiative pushed out a decent 48-page cookery pamphlet from Calabar, with recipes ranging from afia efere to ekpang nkukwo. Recently, a friend discovered a similar artefact on eBay titled What to Eat?: An International Exchange of Recipes, published by a sub-group of the Red Cross called Nigerian Nights Group. The cookbook has 80 pages of recipes, from onunu to Indian rice pudding. While both these books would be termed vanity publishing, I cannot explain my excitement at discovering them: not for their recipes, which don’t showcase anything new, but for their idiosyncratic glimpse into a time and place, just like the Onitsha market pamphlets, or the littattafan soyayya (‘books of love’) written by Hausa women in northern Nigeria since the 1980s. As for Auntie Thelma’s fisherman’s stew, if the ‘recipe’ must exist, it needs to be one that draws in the background of Calabar’s land and seascape. The stew originated on small boats in the creeks, and would have first been cooked by sinewy, hardworking, hungry fishermen around 5am by the light of a small kerosene lantern. This would happen in the cold, quiet darkness of the creeks, watching the day break like an egg into a pan of warming oil, birds turning up, the air indescribably sweet. On a boat moored near the Cross River waters, the fisherman’s stew would be made not from fresh fish, but from a scaly fish called ebori that was almost going off. In the stew, it would scatter and make it swell with its flavoursome body. I imagine that the nuttiness of heated-up homemade palm oil – always the first ingredient in the pot – would sweeten the pungency of the fish in the same way that cooking sake eliminates strong smells. The palm oil is also the gloss on the face of this fisherman’s stew, in which onions are sautéed before blended fresh tomatoes and finely chopped habanero peppers are added. A little tomato puree can be added, too. Catfish, prawns, shrimps, periwinkles and nkonko are steamed delicately in another pot, and added to the simmering peppers almost at the end. Cold-water gari would be the traditional accompaniment for this stew, in which gari and tepid water are added together and set aside until the water is completely absorbed. These are only shards of the secret of the fisherman’s stew – and I imagine part of the anxiety of writing the recipe, or any recipe, is infusing all these elements into the writing, in perfect balance and parlance. CreditsYemisí Aríbisálà is the author of Longthroat Memoirs: Soups, Sex and Nigerian Taste Buds (Cassava Republic Press, 2016) and In The Kitchen: Essays on Food and Life (Daunt, 2020). Hannah Ekuwa Buckman is a Scottish-Ghanaian artist and illustrator based in London. She's worked with The New York Times, Google, It’s Nice That, and many more. She can be found at hannahbuckman.com or at @hannahbuckmanillustration on Instagram. This supplement was subedited by Tom Hughes. The full Vittles masthead can be found here. You’re currently a free subscriber to Vittles . To gain access to our entire back catalogue, you can upgrade your subscription below. |

'There is no recipe, take it or leave it'

02:04

0