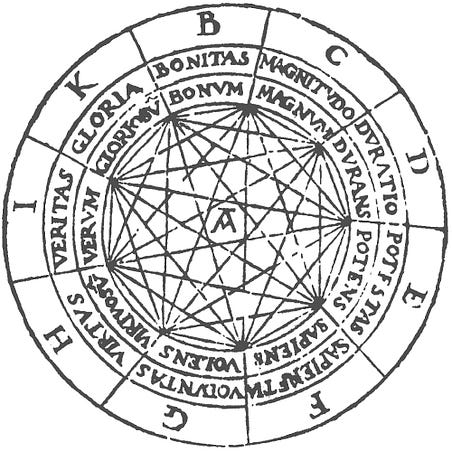

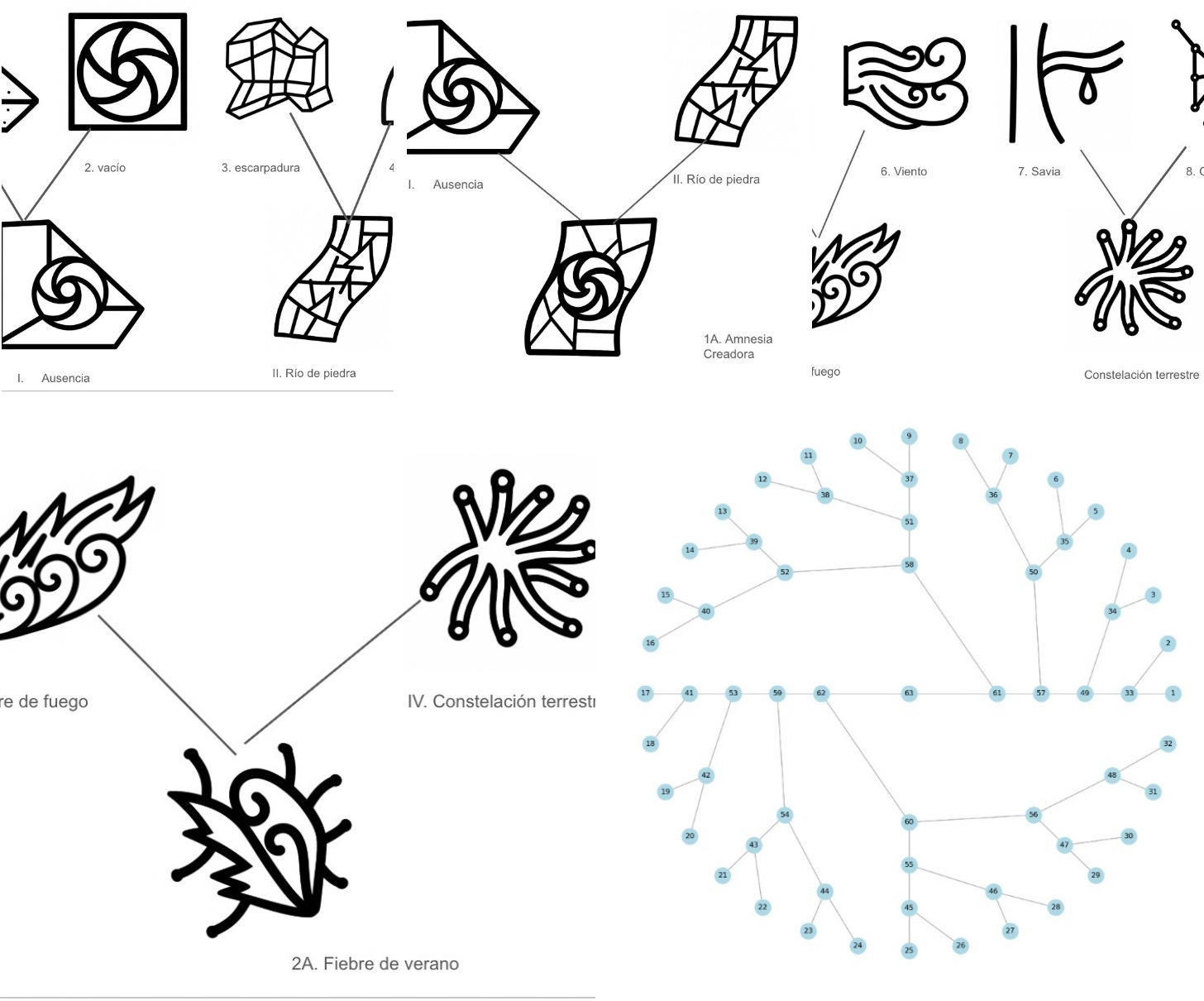

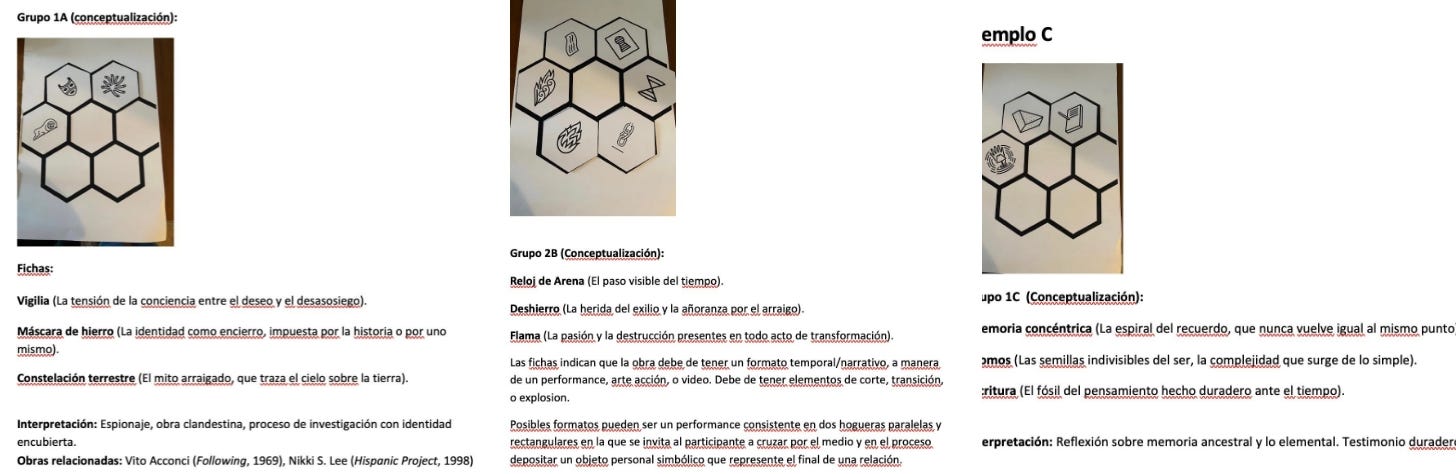

Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia The emergence of fake news, big data, and AI have placed the subject of the production of knowledge (and the distinction between knowledge and belief, as it pertains to fake news) at the very center of practically every aspect of our lives. It is both a scary and fascinating time, but since fear is unproductive I’d rather opt for fascination and make the best of it. This means trying to understand how language becomes power as it reconfigures authority, authenticity, and agency. I am interested in how this emerging phenomenon relates to the history of the utopias of knowledge, which has also and always been of great fascination to me: the aspiration to know it all, the sense that it was possible for a human being to embody all of knowledge (Goethe was famously referred to by his contemporaries as the last living human being who knew everything). This utopian desire has been an everlasting subject in literature, from Goethe’s Faust (where Faust sells his soul in exchange of absolute knowledge) to Milton’s Paradise Lost (the punishment for the pursuit of divine knowledge) to Sor Juana’s Primero Sueño (the dream of total knowledge), and beyond. In our contemporary era, this seemingly impossible quest might be best expressed in the Theory of Everything (ToE): the desire in physics to unify quantum mechanics (the explanation of the world in its smallest form) with general relativity (the explanation of the large-scale structure of the universe). Two thousand years ago, before all this literature and science, we had the Atomists, the Greek philosophers like Democritus and Epicurus, who attempted to do a reductionist philosophy that would reduce all of the universe into a set of principles, both physical and metaphysical. However, it is not until the first century AD, during Roman times, when someone appears with the project to put this systematic cosmology in a treatise format, choosing to use a literary form in order to do it: Lucretius. As someone drawn to tragic antiheroes, I find Lucretius a particularly compelling figure, and Lucretius perfectly fits the bill in that regard (He is rumored to having committed suicide after drinking a love potion). He is the author of “De Rerum Natura” (On the Nature of Things), a 7,400-line poem that seeks to provide an encyclopedic description of the universe. Rumors aside, we practically have no hard biographical information about Lucretius, other that he was fairly ignored during this lifetime —not famous like Virgil or Horace—and his ideas which preceded scientific materialism, were likely ignored as he himself fears in his poem, but he still believes in the necessity of his task: "I fear, perhaps, that you may think I stray [De Rerum Natura, Book I, lines 921–930] While this ambitious aspiration for describing the totality of knowledge might only be a quaint or curious story for science, it is always a fertile ground for art, as I will now try to explain. Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura stands as one of the earliest and most audacious attempts to articulate a total system of knowledge—a poetic theory of everything. While its scientific propositions may now seem obsolete or quaint in the eyes of contemporary physics, the ambition itself remains vital—especially for art. Science eventually moves past the worldviews it once held dear. It refines, replaces, or discards them in pursuit of greater empirical precision. But art does not progress in the same way. It does not discard old truths simply because they are no longer “accurate.” Instead, it inhabits them, reactivates their metaphors, and extracts new meanings from their structures. Where science might demand ever-expanding vocabularies, art often thrives on constraint, metaphor, and translation. Limited systems—when rich in internal tension and symbolic charge—can produce infinite variation. They are not tools for explaining reality but engines for reimagining it. In this sense, the failure of Lucretius’ system to describe the universe definitively is not a liability but a gift for the art practice—because art does not seek objective certainty. It seeks languages that create felt knowledge, structures that spark experience, and systems that model how meaning emerges. De Rerum Natura, in its layered cosmology and recursive ideographic logic, provides precisely that: a limited language model that does not pretend to speak the whole truth of the world, but instead offers a generative framework for navigating it. This is to me a good redeployment of De Rerum Natura today—not as a relic of premodern cosmology, but as a score for creative cognition, a limited language system serving as a scaffold for poetic logic, and a generative matrix of intuitive knowledge. In that sense, art thrives precisely where totalizing knowledge fails—where language is insufficient, metaphorical, constrained, and therefore, most alive.  examples of cards and resulting smaller hybrid sets from previous sets, forming a total of 63 cards I went about creating this card system roughly building on past projects where I created a pedagogical shorthand system— an alphabet of concepts meant to be used to articulate questions toward a project. The same was done here, except that in this instance I based myself on Lucretius’ poem to create the set of images that best represent the various sections of his total system. I felt that De Rerum Natura was a good candidate for a conceptual engine for artistic creation, structured as a limited language model. Inspired by Lucretius’ ancient philosophical poem, this system uses a symbolic lexicon of 32 ideographic cards, which—through a structured, recursive method—are combined into poetic constellations of meaning. These combinations are not meant to yield definitive answers, but to provoke imaginative associations, thematic insights, and the germination of new artistic projects. I would build it around a symbolic language of 32 ideogrammatic cards, each representing a conceptual motif. These images are arranged across six levels of combination and reduction, evoking the poem’s layered approach to describing the natural world. The system functions not as a scientific taxonomy, but as a poetic model of thought—aimed at expanding associations and unlocking new forms of creative inquiry. In this “family” of images the first group would be 32, they would form pairs to create hybrid 16 images/concepts, these would also merge to create a third group of 8, those would merge to create 4, then those 4 form 2, ending with a single image. The process begins by randomly selecting three cards to place at the top of a hexagonal diagram. These serve as the conceptual core of the project. The user then consults the definitions or “nomenclature” associated with each card and reflects on how these ideas might intersect or resonate with one another. Through interpretation, a conceptual framework or thematic direction for the project begins to emerge.  examples of the use of the cards in De Rerum Natura  Workshop participants in Santa Cruz using the card system Once the theme or idea is defined, a second group of three cards is drawn and placed at the bottom of the diagram. These are interpreted in the same way, but with a focus on the potential form or format of the work—such as installation, performance, video, or ephemeral action. This phase encourages the user to think about the medium, setting, and sensorial or narrative qualities that best correspond to the earlier conceptual triad. Unlike AI-driven language models trained to produce continuous text, De Rerum Natura operates with intentional constraints: a fixed vocabulary, a combinatorial syntax, and a purposefully interpretive framework. The user becomes both the reader and the decoder, a kind of creative algorithm who processes symbolic prompts into conceptual blueprints. Rather than offering fixed answers or prescriptions, De Rerum Natura functions as a poetic and intuitive tool—a visual koan, a score for the imagination. It can be used playfully or rigorously, individually or in collaborative contexts such as workshops. The system encourages documentation, reflection, and even expansion: users are invited to modify or evolve the set of ideograms over time. In this way, the project is both a methodology and an evolving language—an artistic limited language model that thrives through constraint, interpretation, and experiential meaning. This model does not speak, but rather aims to elicit speech; like language, it does not speak by itself but it invites others to use it with their imagination. It is not a narrative machine, but a score for thought, and a mnemonic tool for intuition. By limiting language, one can expand the interpretive field, echoing procedural methods from Oulipian constraint writing to Fluxus event scores and ideographic mysticism. The guiding principle is that meaning often arises not from abundance, but from limitation. As I developed this system, I realized—almost sheepishly—that the number six kept surfacing. There are six circles of cards in the diagram, which is the natural progression from 32-16-8-4-2-1. Lucretius’ poem was written in six books, each in dactylic hexameter (the “epic meter” of Latin poetry, meaning the format used for monumental works, such as the ones by Homer). And as a final coincidence, the streets of Santa Cruz, where this project is now exhibited, are famously paved with hexagonal tiles— something that the curators of the project, Akira Ishu and Beni Chan, pointed out to me only well after I was in the final steps of the project.

Invite your friends and earn rewardsIf you enjoy Beautiful Eccentrics, share it with your friends and earn rewards when they subscribe. |

Limited Language Models

04:03

0