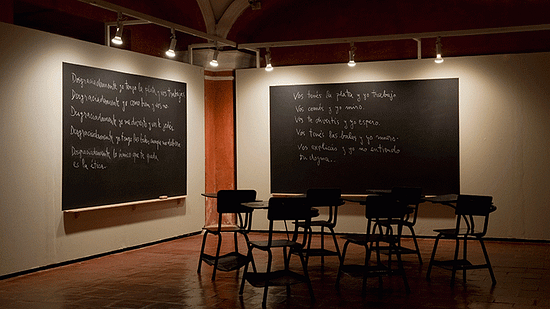

Note: I met Luis Camnitzer nearly 25 year ago, in New York. Camnitzer, a German-born Uruguayan artist who came to New York in 1964, played a key role in the formation of Conceptual Art and institutional critique through a wide variety of media. for more than two decades we have maintained an ongoing dialogue on the subject of education, one that has occupied a good part of our thinking and our work. I share here an exchange we had in the fall of 2023. The original text (in Spanish) was published in conjunction with an exhibition I presented in Mexico City in September of 2023, titled Museo de la vida escolar. With thanks to Eunji Lee for the translation. Pablo Helguera (PH): At what point in your career as an artist did you become interested in the subject of pedagogy beyond traditional art education? Is there a particular moment in your life when education took on a special significance? Luis Camnitzer (LC): I entered the School of Fine Arts in 1953 at the age of 16 to study sculpture. It was a very academic school that focused on realism. The generation of students who were in "power" at that time, all anarchists, were already discussing how to reform the curriculum. The following year, all the union leaders graduated, and suddenly we were without a Student Association (AEBA). My sculpture teacher in the third year, a Stalinist-communist yet a great guy, pushed me to revive the Association because he thought it was absurd that we weren't organized. Additionally, he hoped that we would fight to use the percentage funds for the arts in public buildings to create "Mexican-style" murals. So, I ended up as the general secretary of the Association, with no political or other experience. I reached out to some of the graduates to ensure continuity in the Association's activities, such as re-affiliating with the University Student Federation, continuing the struggle to make the School independent of the Ministry of Education and integrated into the University of the Republic, and continuing discussions about the curriculum, all of which we achieved. This also included forgetting about Mexican murals. In 1956, I received a scholarship to study at the Munich Academy, and in 1957-58, I was tasked with an official mission (and the corresponding passport) to study curriculum structures. When I returned, there was a new generation in AEBA, and we continued working together on the development of a curriculum, which we managed to implement in 1960. The plan was inspired by the pedagogies of Dewey, Montessori, Decroly, etc., and the models of Bauhaus, Ulm School of Design, Kassel School, and the Chicago Bauhaus version. In this way, we were a decade ahead of many things that Joseph Beuys later proclaimed as his pedagogical revolution. I tell you all this because my entry into pedagogy was not through direct teaching but through the anti-academic curriculum structure. Throughout the struggle to impose the curriculum, the Central Council of the University intervened in the School and removed the director. Academic professors demanded that the director be reinstated and the intervention be suspended, with a threat of mass resignation if this was not done. With the help of the Student Federation, we managed to keep the intervention in place. The professors resigned, and therefore the University had to open positions for new teachers. The Student Assembly decided that three of us should apply for these positions, not to win but to serve as a reference for the other candidates regarding the new curriculum. Unexpectedly, three of us won the competitions. We were scared and returned to the Assembly to see what to do, and it was decided that we should accept the positions for five years with the mission of helping to train new teachers. This is how I started teaching art (in printmaking), although my original primary interest had been to help reorganize the institution. PH We undoubtedly share an affinity for anti-institutionalism and anti-academia. But I think it's important to define exactly what we mean by these terms, starting with the term "academic." As you know, my formation as an artist actually took place in the education departments of various museums—indeed, a much more valuable education than the formal training I received in art school because my work in museums was not based on solitary work in the studio but on the daily task of connecting the public with works of art. Because of this, to me, the term "academic," beyond the conventional notion of 19th-century realistic art, generally represents the homogenization of terminologies and the transformation of every creative process into a series of recipes, whether it's the creation of a still life or a conceptual work. It's ironic that for 13 years, I was the director of academic programs at MoMA—a period during which I sought to de-academicize the museum's pedagogy, much to the chagrin of academics. As for the term "institutional," I'm afraid that I've always been much more institutional than you—a quality I admire in you. For me, working within existing structures is important, so I consider myself somewhat of a hermit crab, seeking to inhabit these structures in order to change them, even in my work outside of my museum work. My most extensive pedagogical project, La Escuela Panamericana del Desasosiego, was precisely a simulation of the institution but with an experimental structure. I believe that you, on the other hand, are much more radical and aim to tear down existing structures to build new ones, but I'm not sure if I'm mistaken. What is your interpretation of both terms? LC Yes, we have to be careful with words, especially those with multiple meanings. Here, I used the word "academic" in relation to the 19th-century French Academy. Most of the more contemporary professors at my school had studied with André Lothe, and they all believed that one had to start with copying from nature before attempting to break the rules. They used Picasso as an example, without understanding that the poor guy didn't have alternatives given the time he was educated. I think the difference between you and me, perhaps aside from temperaments, lies in where and how we were shaped. I've come to realize that, even though I was always very obedient to family rules as an only child, once I entered art school, everything came down to the location of power, its administration, and the interests it serves. In that sense, the generation that preceded me, which was openly anarchist and introduced me to the thoughts of Martin Buber and Herbert Read (i.e., an ethical and communal anarchism), found fertile ground in me. The communist professor I mentioned, Armando González, who kept a bust of Stalin in his studio during the Khrushchev era, recognized this in me and, with great pain in his soul, told me not to try to be realistic and to follow my expressionist instincts. At the time, I was a terrible draftsman and always failed my drawing exams, but the liberation the professor gave me led me to analyze the distribution of power between me as the author and the pencil as a tool. Adjusting that distribution, creating horizontal teams of interlocutors for a common task, allowed me to adjust not only my art but my political ideology. Today, in my very old age, I understand that I have always been more interested in education as an instrument of formation than art as a mechanism of production. In this sense, it's not about demolishing institutions but finding the fissures through which they can be guided to achieve that purpose. I believe this is where you and I are in strong agreement. By the time the institution operates, it generally adheres to plans that are already outdated and invalidate much of what they manage to do. But at the same time, they give us, those who disagree, the credibility to criticize them. Without institutions, this criticism is not effective because there is no sounding board. One of the first museums that bought my work was MoMA in 1962, but it was in a way that made me feel exploited. I decided then that my mission was no longer to get museums to collect me, and not even to try to destroy them. My mission was to collect museums. The bigger my collection, the greater my credibility, and therefore, the greater the echo of my criticism. I remain involved in art because it is the field that allows me to work with the fissures, and without institutions, there is no possibility of fissures. Today, for example, the famous "educational turn" has been institutionalized, and I believe it no longer serves to achieve an equitable distribution of power. That's why it seems to me that it's time to enter a period of an "artistic turn" that changes education to make it critical and imaginative. We want everyone to see and use the fissures, thus expanding the horizon. I fear I'm compressing a lot in this response, but I don't want to abuse your space. PH This conversation is starting to generate various facets I'd like to respond to; let's see if I can. Another difference between you and me is that I am the youngest of four siblings, them being much older than me. As a result, I believe I had an ideal situation: more freedom and many teachers (my parents, my brother, and my sisters), especially my brother, who was a philosopher and had me read existentialists and a lot of literature. He wasn't really interested in political thought; this was an interest I developed due to my adolescent fascination with social realism (which was clearly anachronistic; one of my high school teachers used to make fun of me for being interested in 1930s art in the 1980s), but it evolved, especially when I moved to Chicago. Regarding the idea of finding fissures and exploiting them and the artistic turn: indeed, the "educational turn" was a passing and somewhat brazen trend, using pedagogy as an idea to help validate curatorial reputations that weren't really committed to the transformative power of education that you describe. But of course, education is not a fad, and I believe that those of us interested in pedagogy have been doing it before, during, and will continue to do so after any trend. As for your definition of the "artistic turn," I would like to know to what extent this is linked or equated with pedagogy as an artistic work in itself and the difficulties that arise from doing so. Many of the pedagogical projects I've undertaken, I see them as artwork, but museums and contemporary art institutions struggle to see them as such. For instance, a few years ago, I led an experimental workshop in Mexico that I specifically requested to be presented as an artwork, titled "Theory and Practice of Limbo." The organization that supported me, which no longer exists, supported me in all aspects of the project, but in the end, we couldn't present it (could I say "package it"?) in a way that the entire workshop appeared as an artwork or performance. What I mean is that education is still seen as something external to art, not as art in itself. How do you see this relationship, and to what extent have you thought of your work as an educator as art? LC I always missed not having brothers and sisters. The only child carries an overwhelming filial burden that in some ways distorts one's view of the environment. But that's a good question about accepting educational projects as artwork. My project "The museum is a school" is generally seen as an artwork, despite the contract that accompanies it. By calling it "art," its political function is dulled, which consists of making institutions enter into a contract with the public, where the public can file a lawsuit against museums adhering to the declaration but not fulfilling the "contract." I often say that if I were the emperor of the world, I would prohibit the word "art" because it causes us more trouble than good. To me, art is fundamentally a way of confronting, processing, and generating information, in other words, a way of knowing. It is a meta-discipline of knowledge because it not only encompasses computable information but also does not necessarily adhere to existing codes or principles governed by logic. It allows us to go beyond the describable, create our own codes, and, more importantly, open up the imagination to the illogical, the absurd, and the impossible. Once we place ourselves in the realm of impossibility, we can evaluate the reasons for impossibility and the interests served by its definition, and negotiate with the reality of what is possible. This is also an investigation into power: what are the obstacles, who put them there, which interests benefit from their existence, and how to remove them from the path. It is this aspect that makes artistic work essentially a political task (who has power, why they have it, and why we don't). From this perspective, art is a meta-discipline because it is not an alternative to scientific thinking but includes it as one of its branches. If we understand art as the most complex and holistic way of the act of knowing or as a way to give a comprehensive (even if fictitious) order to the universe, this automatically defines how education should be in its entire process from birth to death, not just from preschool to postgraduate. It would also expose the danger of STEM education, which reduces education to what is applicable and profitable, gradually eliminating speculation and imagination. STEM makes us believe that education is training and that art is ingenuity rather than the exploration of the unknown. I believe this identifies something on which we may possibly disagree: for me, politically, it's not about expanding the word "art" to accommodate educational projects, but changing the educational process to accommodate and promote limitless imagination, regardless of the name we give to the results. Maintaining "art" as a separate disciplinary space fragments the act of knowing and allows the objectification of its results, isolating them from the process of social construction. PH I'm not sure we disagree all that much, really. I wholeheartedly agree with the idea that art is a way of knowing and generating knowledge. On the other hand, I've always been aware of the danger of categories and labels, and I've also been convinced that what matters is not whether something is called art, education, etc., but the effect it produces. When a person declares that something they see in a gallery is not art, their comment indicates that in their mind, this person has an implicit idea of what is art (e.g., academic art from the 19th century, for example). As an educator, I like to engage with these comments because they spark good discussions. As an artist, my attitude is usually one of acceptance because it's irrelevant to me whether the experiences I provide to a person are considered art, education, or something else. I believe that one's experience of a work cannot be truly articulated in words or any kind of definitive reflection. But my perspective is that while terms may not matter, we also have no choice but to work within existing conventions and expectations because our ability to break, alter, and reimagine them helps us connect with the audience familiar with these conventions and allows us to help them generate new ways of thinking. Therefore, I believe I have to understand art as a language. That is, I think art operates in the same way as a language, albeit relying not only on words but also on physical elements (that produce sensory responses) and symbolic elements (that produce emotional, intellectual, etc., responses). Hence, you and I have to accept being called artists because we use that language. Being an artist is a category that we need to do what we do, in my view. It's like Wittgenstein's ladder—it helps us get where we need to, and then we can discard it. But it seems important to me to defend the term "art" as a space to act freely according to the rules we deem appropriate. Perhaps it's a bad word, but it's necessary. I'm not sure if I'm making myself clear. But my main question, definitions aside, concerns the role you see museums (or any other institution) playing in preserving your pedagogical work. Of course, your "art" works from the 1960s onward, including photography, printmaking, etc., can be preserved in traditional ways, but your work goes far beyond the object. I have sometimes wondered if the art-education work I do is more of a methodology that should be continued like any other educational methodology (Montessori, Reggio Emilia, Freirean pedagogy, etc.) with its natural reinterpretations and adaptations that any methodology undergoes. Have you ever thought of your work in that way? LC Certainly, in that sense, being described as artists doesn't bother me too much. What does bother me is, on one hand, that as artists, we might end up believing ourselves to be such in the restricted definition, thus losing sight of our activity as "knowledge workers." On the other hand, it allows the word to reaffirm the artisanal production of the finished product. When you're asked about your profession and you say you're an artist, people always ask if you paint or what technique you use. If you were to say you're a philosopher, they would ask you about the ideas you work with and not whether you write by hand or on a machine. The point is that art is what I call a "craft plus," where it's the presence of the "plus," that something that doesn't fit into the traditional code offered by spoken or written language, that decides whether the activity is art or not. The only thing we can say is that precisely because it's indescribable, that "plus" (or the part that produces what you call "experience") expands knowledge. This is what sometimes frustrates me with some manifestations of "art as social practice." The results often exhaust themselves in description. Although they may improve a social situation, they do not affect or enrich the way of knowing. An imaginative social service remains a social service and can even become a political action. But the imaginative twist given to it only achieves a refinement of craftsmanship without transcending craftsmanship. And the fact that I'm an artist doesn't mean that everything I do is art, or that I should be protected if I do something unrelated to artistic pursuit that, if I were an ordinary citizen, could subject me to some form of punishment. As for my work, since the sixties when I abandoned expressionism and delved into conceptualism (or "contextualism," as we defined ourselves with Liliana Porter and José Guillermo Castillo before the term "conceptual art" was coined), I was always aware that I was working with problematizations, and these, secondarily, had to take on a "presence" to communicate. But precisely because I came from a craft background (first sculpture and then printmaking), and because my initial approach was to challenge the limits imposed by technical definitions, it was clear to me that it was about the interest in the problem rather than the perfection of the packaging. The interest in the problem, or its solution, is not in the literal but in the presence of the "plus." This conception of problematization defined that everything I did was fundamentally educational, and that the fetishistic collecting of the object was of no greater importance beyond economic benefits. It's about sharing the risk of speculation and thereby helping others explore the limits of their way of knowing. It's a collaborative effort where the artwork must retain its quality as a trigger rather than becoming an icon. This is where art and education are so closely linked. For me, the success of both the teacher and the artist is demonstrated by their becoming unnecessary. Museums generally assume that the works they display are icons. If they were seriously concerned about education, they would understand that the icon represents an antipedagogical distribution of power. The icon demands admiration and submission, and it is the collection of icons that generally makes the museum a place of ostentation rather than education. The traditional and banal image of the museum as a church is not inaccurate. The canon does not like heresy, and yet it is heresy that allows us to question dogma. It's the challenge of the work through "miration"[1] rather than "admiration" and how this affects our daily decisions that gives educational value to a museum visit. An educational museum would underline this activity and measure its success not by the number of people who pass through its space, take selfies, and buy souvenirs. Instead, it would measure the impact that the museum experience had on the daily decisions of the visitors. Impact assessment would be much more useful than the usual measure of popularity. It would affect not only the internal policy of museums but also the external one. It would present the need to move away from the current model of an occasional open vault and instead work with schools to achieve curriculum revisions that complement STEM and ensure that people imagine before consuming. I believe that as artists, this is the task we need to promote, not the personal fame of the artist. PH I love your definition of artists as "workers of knowledge." I believe that many artists working in the social sphere implicitly identify with this notion without necessarily articulating it this way. I think this is why the term "social practice" is used in English, explicitly removing the term "art." Mierle Landerman Ukeles once told me that she despised this term because it made her feel as if an artist's profession was more like that of a therapist. But the use of the phrase reveals a discomfort, as you describe with the word "artist," which indeed implies a craft-like production of objects. I'm not prepared to abandon the word because I believe we should redefine it rather than allowing others to use it in a way we consider wrong. Perhaps I'm an idealist. Regarding your impatience with this type of work, which I sometimes share, especially in the case of many works that boast of being transformative more in their description than in the way they function in real life, one problem that arises from creating art that integrates into social or educational contexts is that it becomes elusive to criticism: if you criticize it as art, it is argued that it is education, and if you criticize it as education, it is argued that it is art, thereby seeking to become immune to analysis. The question we then have is how to evaluate this type of work, just as you talk about how we evaluate the impact of a museum experience on a visitor. As an educator in museums, where we always had to thoroughly evaluate each activity, initiative, workshop, and obsessively debate measurement parameters, I found it contradictory that an artwork presented as pedagogy was exempt from the same type of scrutiny as a regular educational project. I completely share your perspective about the emphasis given to STEM in the modern world, although in terms of science and technology, there is a focus on assessing and measuring results, which can be quite beneficial from their methods. I don't want to overextend in this conversation, and you've already given me a lot of your time, for which I'm very grateful. But I need to close a topic with you, which has to do with your legacy as an artist. As you rightly point out, museums tend to turn everything into an icon or fetish, but I believe this is partly because artists don't offer them many alternatives. I recall that when I worked at MoMA on a retrospective of Lygia Clark, one of the most challenging issues the curatorial team faced was how to present her therapies - i.e., the kind of activity that Lygia declared was not art because she had officially renounced being an artist when she decided to start doing therapies. They were, on the other hand, individual experiences and long-term processes, not spectacles or performances. In the end, we invited two of Lygia's former assistants (who still conduct therapies, Lula Wanderley and Gina Ferreira) to train our educators to provide some kind of demonstrations to the public. It was by no means perfect, but to this day, I don't know how else it could have been done if the goal was to share this crucial aspect of Lygia with the public. The therapies are not art, so they should not be subjected to the fetishistic treatment of something hung in a gallery, but the "demonstrations" were carried out in the last room of the exhibition, making it quite ambiguous. So, my point is this question: What options can an artist provide to a museum to preserve and maintain their thinking beyond exhibiting their works? How can an artist keep their work alive without fetishizing it? LC Lately, I use the simplistic image of a "tree of knowledge," where I place art as the root activity in its cognitive function, as language in the trunk, and as a discipline producing "fruits" in the branches. For me, the important part is the root activity, but the word "art" is used for everything, making it unclear what we are talking about. Applying quantitative evaluation systems becomes even more confusing because they are not designed for the most important aspects of art, which are located in the spaces between the units and not within the units themselves. These spaces are what we lose with STEM, and in the long run, we will end up failing to perceive them. However, this doesn't mean making the opposite mistake and ignoring the units. That would be confronting one form of knowledge fragmentation with another. I recall your quote about the group that did an educational project, and when you asked about the educational consequences of the project, they replied that they didn't know because it was a work of art, and they were artists. Regarding Lygia Clark, part of the problem is the family, which encourages the fetishization of her work for their economic interests. I tried to reproduce one of Lygia's works in my "Didactics," and they wanted to charge an absurd amount for rights, even though it was an obviously non-profit academic book. I ended up using a page from a catalog that reproduced the work, presenting the catalog openly to evade the issue. I didn't find the Lygia Clark exhibition at MoMA very good precisely because it emphasized the works too much and ended up being dull. But the participatory aspect seemed well done to me. I didn't know it was your contribution, although I could have imagined it. That could have been the backbone of the entire exhibition, and then she would have appeared in all her power. But this is precisely the problem with museums; they get trapped in the objects and, in doing so, imprison the viewer's perception. The museum looks at the work, and it leads the spectator to do the same. When the museum is somewhat more progressive, it tries to enter the work and help the viewer do the same. But cognitively, this always uses the work as if it were a tunnel. I prefer the idea of going around the work to position oneself behind it, alongside the creator, to confront what motivated the creation of the work and see if it serves as a response to an interesting question or as a path of inquiry. This is where the "root" part of art is shared, and it initiates an educational process. The artist can revisit their own work in these terms and then help the museum do the same by demanding that this approach to accessing art is used. Along the way, the artist also learns to differentiate whether they are only navel-gazing or contributing to social construction. The fetish or economic value of the work corresponds to another field that has nothing to do with all of this. On the one hand, it's like confusing the beauty of calligraphy with the content of the text. On the other hand, it's like confusing the value of a manuscript signed by Simón Rodríguez or Paulo Freire with the cognitive consequences of what they are telling us. But in this confusion, artists are as guilty as museums, or at least we support each other in the same vicious circle. [1] From the Spanish, “mirar” (to see). You're currently a free subscriber to Beautiful Eccentrics. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Of Workers and Trees

04:01

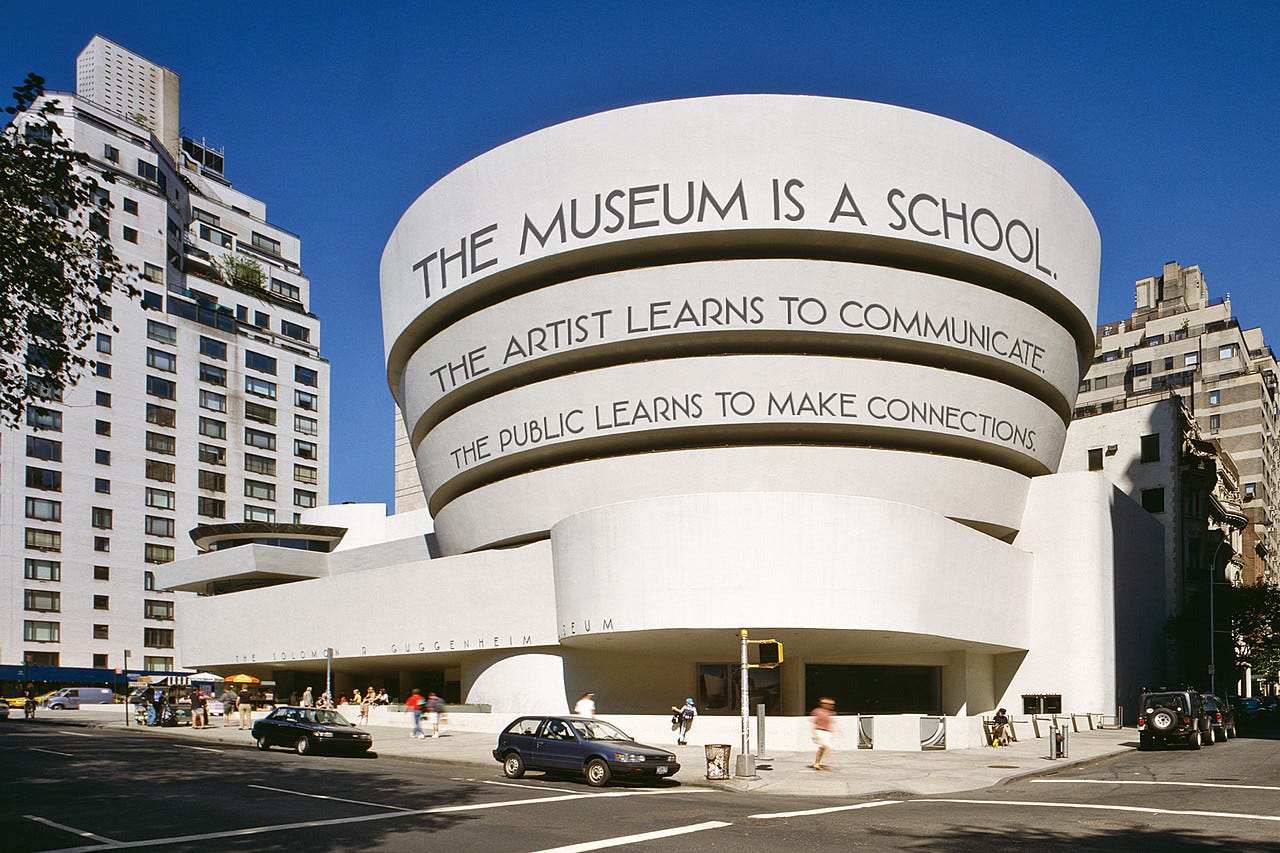

0