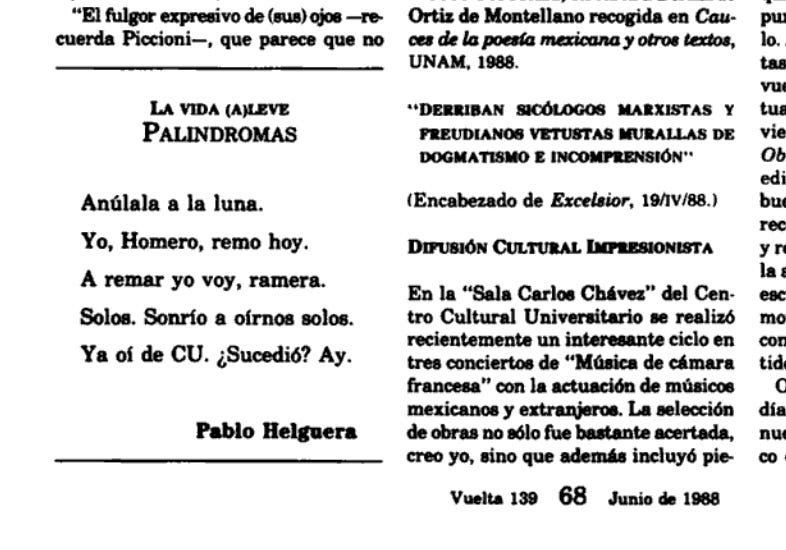

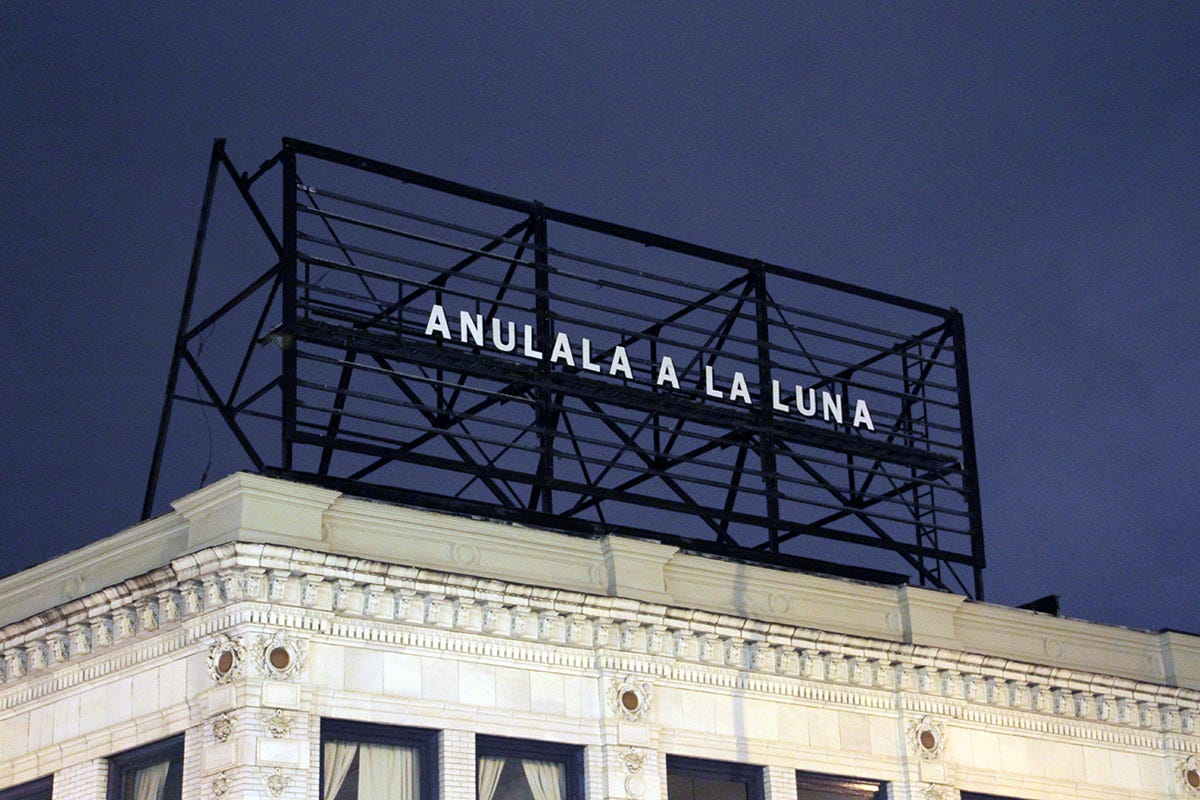

In 1967, the Maltese psychologist Edward de Bono (1933-2021) published the book The Use of Lateral Thinking. This unusual and fascinating book, is, in essence, an attempt to study, theorize, and give structure to what we mean today by the phrase “thinking outside the box.” I relate a lot to what de Bono argues in his book because he links problem solving with humor: creating unfamiliar patterns to solutions — stuff that in his view departs from “vertical thinking”— can create unexpected, and often whimsical approaches. De Bono’s breakdown of lateral thinking approaches ( Provocation and random entry for idea generation, movement techniques, challenge, concept formation, disproving, and fractionation) have never been fully adopted by psychology and in fact has at times been deemed as pseudo-psychology. However, the term “Lateral Thinking” has gradually gained acceptance in the study of creative problem solving, and some have even linked them to Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences (particularly visual-spatial intelligence, which is why this way of looking the uses of the mind is worth considering for those interested in the mental process involved in art making). Earlier this year, in January of 2024, a team of Israeli and Ukrainian researchers published a paper that assesses lateral thinking through verbal tests. The study resonated a lot with me because it made me realize that a practice that I have followed since childhood likely involves a form of lateral thinking: palindrome writing. I started writing palindromes as a child, mainly as a game with my brother. Palindromes are words or phrases that can be read equally backwards or forwards, such as “madam” or “racecar”. In Spanish, classic examples are “Amor a Roma”, “Anita lava la tina” (“Anita washes the bathtub”), “dábale arroz a la zorra el abad” ( “the abbot was giving rice to the fox”) and the wonderfully surrealistic “odio la luz azul al oído” (“I hate blue light onto my ear”). In 1988, when I was 17 years old, I wrote a group of palindromes that my brother surreptitiously snuck into Vuelta magazine (likely while its directors Octavio Paz and Enrique Krauze were distracted) but with the enthusiastic approval of the editor, Aurelio Asiain. The palindromes included “Anúlala a la luna” (“delete the moon”) “Solos, sonrío a oirnos solos” (“alone, I smile at us hearing ourselves alone”) and even a political one that referenced a recent student strike and demonstration at the University of Mexico’s Ciudad Universitaria campus (“Ya oí de CU. ¿Sucedió? Ay.”) A criteria good palindrome writing (if there are any formal criteria anyway) is that the phrase needs to be not only grammatically sound, but that it should be more than mere nonsense ( also, a mere laundry list of words does not a great palindrome make). For that reason, it is a fertile ground for poetic approaches, because the palindromic structure sustains itself on metaphor, allusions, and humor.

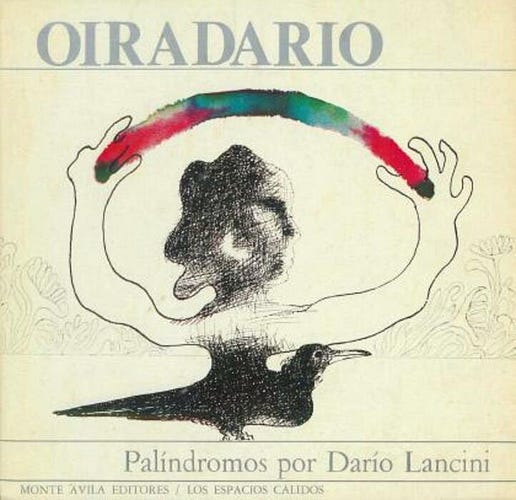

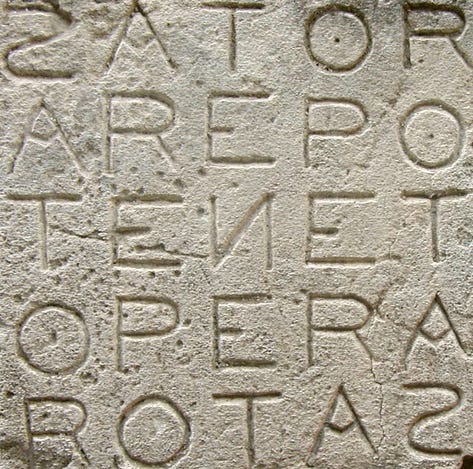

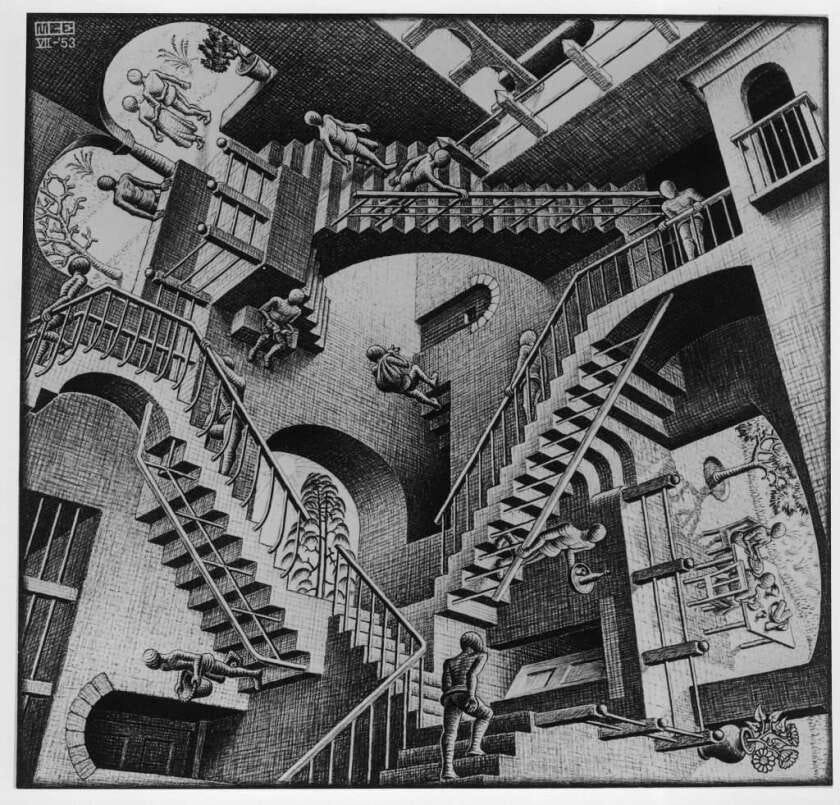

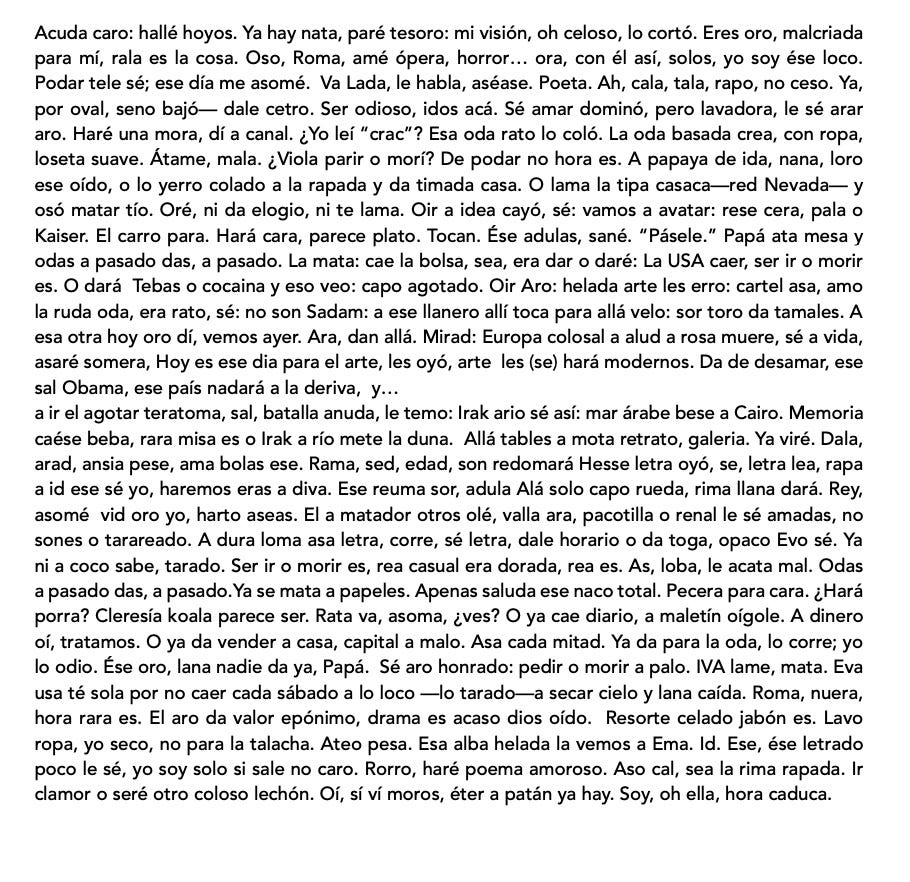

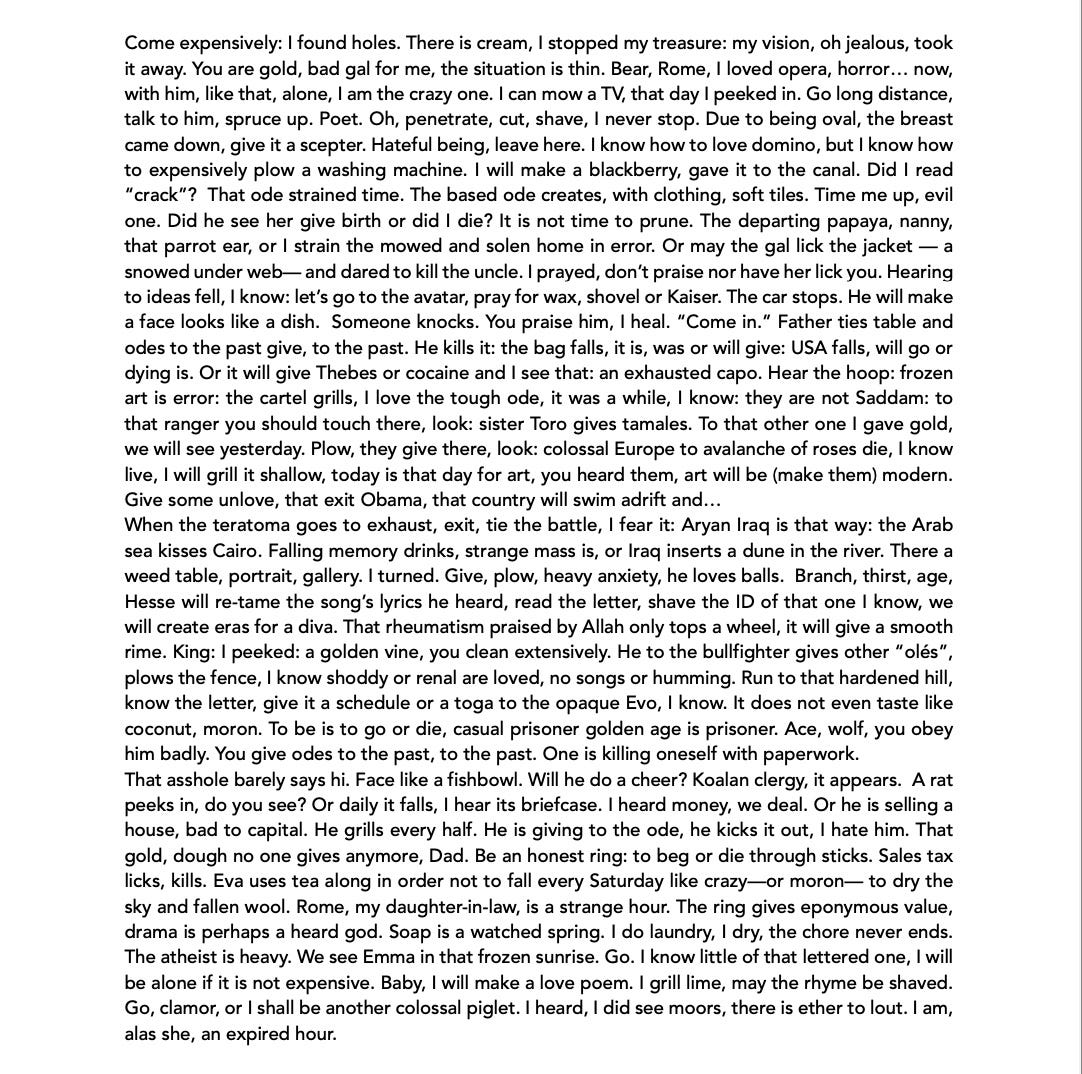

Shortly before my palindromes were published, my brother brought me to meet the poet Juan Almela, a.k.a. Gerardo Deniz, who was on the editorial council of Vuelta. Deniz was born in Spain but arrived in Mexico as a child, his family exiled due to the Spanish Civil War. He was (and I don’t ever use this word lightly) a genius: one of the most erudite and original poets of his generation in Latin America who has yet to receive due recognition. He studied chemistry and was able to translate from Russian and Sanskrit; his poetry used extreme hermeticism in the true modernist tradition of Eliot and Pound but adding scientific terminology that would have confounded those modernist poets. He also incorporated colloquial structures and occasionally mixed in vulgarities and school yard humor in very effective ways. He was an oracle of sorts who my brother and his friends admired deeply. He lived in Mexico City in a small apartment on Avenida San Antonio in our neighborhood, Colonia Nápoles, across the street from Panadería La Luna. The evening, we visited we brought him a chicken pot pie that my mother had baked, an offering of sorts. He seemed to me a bear of a man, with slicked back white hair, goatee, and thick glasses—and, as I recall nearly or totally blind in one eye— moving slowly like an iceberg. We sat in his living room, completely hoarded with books and so dimly lit that we almost were in total darkness. He nearly did not move at all when he spoke, and did not seem to even look at us while doing so but to an undefined point in the distance in front of him. When he spoke, his every phrase was perfectly crafted, witty, and to the point. We started discussing palindromes, and my brother showed him the ones I had written. He liked them, and was very friendly. He said: “I love palindromes, I used to write them. Here is one I wrote once”. He then took a piece of paper, and completely by heart and in a matter of two minutes he wrote the following perfect long palindrome: Acá, como coloso, y notar o dominar. Átame mal la roma severidad, ni la dama Eva usa la mar. A pata yo voy allá. Allí sal, allí peces, allí Lolilla se cepilla la silla. Allá yo voy a tapar a mala, suave amada linda. Diré: “¿Ves, amor?” Allá me matará: “Ni modo, ratón, yo sólo como caca.” [Here, like a colossus, and noting and dominating. Poorly tie me in the dull severity, not even lady Eve uses the sea. I walk there by foot. Come out, fish are there, there Lolilla will brush the chair. There I will cover the evil soft, loved beauty. I will say: “do you see, love?” There she will kill me: “never mind, mouse, I alone eat shit.”] My brother and I were stunned. It was a scene like the one on the film Amadeus, where Mozart plays Salieri’s dull composition by heart after hearing it only once and recomposing/improving it in real time. Then, after a brief silence that followed his palindromic lesson, the immovable Almela said: “and now, I am going to consume a big slice of your Mom’s chicken pot pie.” Perhaps the greatest Spanish-language palindromist of all time was the Venezuelan Darío Lancini (1932-2010), who was part of the literary and visual arts avant-garde group El Techo de la Ballena. His book Oír a Darío is kind of a bible and textbook for Spanish-language palindromic practice, starting with simple (but highly ingenious) phrases and moving on to even creating a palindromic play. Lancini’s involvement with El Techo de la Ballena is particularly relevant to me because, in contrast to other 20th century poetic practices, I have not been able to find many palindromists who aligned with the visual arts (such as surrealist poets, or even concrete and neo-concrete poets did). Palindromic poetry offered an opportunity to conceptually merge the visual and the textual, not least because the symmetry of the palindrome operates in both narrative and visual senses, as exemplified by what is arguably the most famous palindrome/anagram: the Roman Sator Square which contains a multi-directional five-word, acrostic, Latin palindrome. The question pertains partially to an issue around the use of text in the visual arts, which up to now has retained the general definitions established by Lawrence Weiner: language as material, not as literature. Palindromes, however, exist somewhere in between. Palindromic visual pieces that use compositional virtuosity is mostly seen as design, not as art, with perhaps a few exceptions such as Op Art. M.C. Escher is an example of a visual palindromist that is typically revered by non-artists and young art students (as was my case, when I was young); his drawing paradoxes are curious and visually appealing, but maybe because of how they exist in a realm of their own and never quite aligned with any particular discourse, conversation or thread in modern art, he is generally seen as marginal, a producer of one-liners and an impressive but stand-alone anomaly. When I asked my friends about Escher in social media the reactions I received about him were strong. With the exception of a few fans, the majority were mostly dismissive and even mean, with comments that included “outlier”, “overrated”, “trick illustrator”, “poster artist for college dorms” “irrelevant to art history”, “soft-avant garde, closer to graphic design than high art”, “clever but marginal for modern art”). He is an artist of whom the most famously study was done not by an art historian but by none other than a cognitive scientist, Douglas Hofstadter, who used the concept of “strange loops” and isomorphism to tie Escher’s mathematical drawings with Bach’s compositions and the logic of Kurt Gödel. Escher is a good example of how even the most inventive plays with form can’t make up for content. Such is also the challenge with palindromes: like a poem, a palindrome should be more than about the virtuosistic arrangement of words. But, I would argue, therein also lies its potential beauty: it is a form of constrained poetry of which strength lies in both the ability to structure a grammatically sound sentence (or for that matter, imagery) that may also produces meaning. In any case, as far as formal aesthetics are concerned, palindromic music does find one of its highest expressions in JS. Bach, a master of the Baroque contrapuntal and fugal techniques. The notion of having two or more intertwining voices (melodies) in a composition fits well within palindromic aesthetics, which in essence is about creating a piece in two opposing directions. The best example of this in Bach is his famous Musical Offering, also known as the Crab Canon, a palindromic masterpiece here visualized in the form of a möbius strip:  The title Crab Canon was not given by Bach but by others at a later period, using the latin musical term canon cancrizans, which in turn refers to how crabs are known to move backwards as well as forwards. In 2009, I was invited to present a performance at the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid. I performed with my sister, the pianist Beatriz Helguera-Snow, who played palindromic works by Josef Matthias Hauer (1883-1959), Robert Starer (1924-2001), and Witold Lutoslawski (1913-1994). For it I wrote a palindrome that is in some ways an anthology of my previous works, which in aggregate runs 612 words. I don’t claim it being the longest palindrome in the Spanish language, but it seems to me that it exceeds the length of those by Darío Lancini. I enclose the translation below (I include the original and the translation as images as they exceed the word limit of Substack posts). It might be relevant to note, as a footnote (and some of you might have already considered), that crabs move faster and easier when they go sideways, which is the easiest direction for them given their body structure. For that “lateral thinking” reason you could say that crabs are organic palindromists, and that palindrome-making might not be a mere parlor game of contrived word artifice, but could aspire to be, perhaps —especially if it manages to transcend virtuosistic form— a form of straightforward naturalism. — [with thanks to Lorena Marrón] Invite your friends and earn rewardsIf you enjoy Beautiful Eccentrics, share it with your friends and earn rewards when they subscribe. |

Crab Canons

04:02

0